I taught leadership for about 15 years, and I had a moment about four years ago when I realized I was teaching something I couldn’t define. This is actually a running joke in leadership studies, so let’s get it over with.

As far back as 1959, Warren Bennis said of leadership, that “of all the hazy and confounding areas in social psychology, leadership theory undoubtedly contends for top nomination.” Since then, things have probably gotten worse, since there is now servant leadership, complexity leadership, shared leadership, emergent leadership, mindful leadership, Indigenous leadership etc. For any number of reasons, some of these theories are quite hazy, indeed. Some, like shared leadership, need further research. Others, like Indigenous approaches to leadership, are finally being recognized and brought into formal study.

Another example: “leadership is one of the most observed and least understood phenomena on earth.”

This has gone on so often that by 1991, Joseph Rost chided leadership studies authors for making a couple of ritualistic comments in the course of their articles about the definition of leadership. The first statement goes like this: Many scholars have studied leaders and leadership over the years, but there is still no clear idea of what leadership is or who leaders are.”

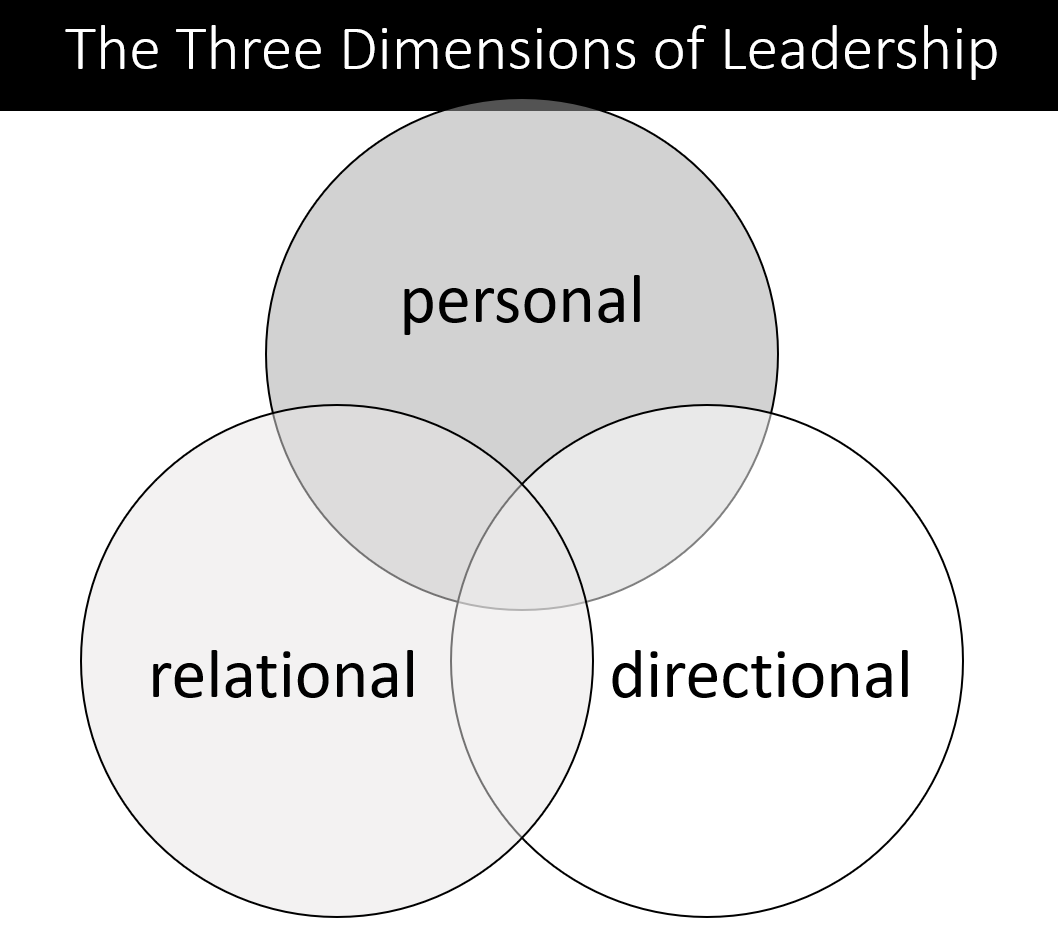

I don’t think that’s true. I don’t think I could give a definition of leadership that someone couldn’t pick apart, but whatever definition of leadership we use, there are generally three main dimensions.

Leadership is personal

The first dimension is that leadership is personal. The American poet and activist Muriel Ruykeser once said, the world is made up of stories, not atoms.

Bennis and Thomas (2011) suggest that personal meaning for leaders often arises from a crucible, "a transformative experience through which an individual comes to a new or altered sense of identity" (p. 101). Such experiences can include a violent, life-threatening event, the experience of prejudice, or a period of deep self-doubt. These crucible experiences build what Bennis and Thomas call 'adaptive capacity,' or "an almost magical ability to transcend adversity, with all its attendant stresses, and to emerge stronger than before" (p. 112).

As Callahan and Martin write, we each must understand that one thing that holds the secret of our life. Each of us lives with our own story – a narrative that defines who we are and contributes to leadership effectiveness. How well a leader knows and is defined by their story – whether it is an illness, a near-death experience, the experience of prejudice – these crucibles have a non-spurious relationship to leadership effectiveness, meaning if you know and are leading your story, you have a far greater chance of being a successful leader, no matter what you are doing.

One of my favourite leadership articles is Beware the Busy Manager. In their observation, they found that only 10% of managers are adept at using their time and energy. And one of the important differences is that purposeful managers work from the inside out. Purposeful managers decide first what they must achieve and then work to manage the external environment. A sense of personal volition characterizes the purposeful manager – the refusal to let other people or organizational constraints set the agenda.

Purposeful managers are also skilled at finding ways to reduce stress and refuel. They commonly draw on a "personal well" - a defined source for positive energy. Some work out at the gym or get involved in sports. Others share their fears, frustrations, and thoughts about work with a partner, friend, or colleague. Still others refuel their inner reserves through hobbies like gardening.

Some of the worthwhile questions at this point are, what’s your leadership story. Why should anyone be led by you? Why do want to lead? Who do you want to lead? What difference do you want to make in people’s lives? In your community? What are you being called to do?

I think these are essential questions, and sometimes, we are facing struggles and difficulties at work because we have lost contact with our soul. If we can clarify our story and remember why we’re doing what we’re doing, perhaps everything will become more focused. So the most important relationship is that relationship with self.

Leadership is Relational

Once we get that relationship right, then perhaps we can lead and manage the rest of our relationships in our lives. Leadership is relational. At its most basic level, we have the relationships inside our teams and outside our teams. Effective leaders are intentional and deliberate about the internal culture they are creating with their teams, and they cultivate transformative relationships with partners.

We now know the importance of networks. As smart as you are, if you can build a strong network, it will make you better. And sometimes, you will have to advocate to change the world. Some ways of conceiving the relational nature of leadership include:

Tikkun: Tikkun is the the Jewish notion of helping God to repair God's universe (Grigg, 2008, p.60). Including the concept of Tikkun (and any religious reference) may be automatically controversial for any number of reasons, but this religious concept of repairing a damaged world holds an important part of leadership as healing; leadership as connection to both the human community and the community of life.

Erich Fromm suggests in the Art of Loving that "to be concentrated in relation to others means primarily to be able to listen" (p. 105). This practice of listening is a practice of love, and listening includes listening to Self. Fromm suggests, "the main condition for the achievement of love is the overcoming of one's narcissism" (p. 109), which requires the ability to see the difference between "my picture of a person and his behavior, as it is narcissistically distorted, and the person's reality as it exists regardless of my interests, needs, and fears (pp. 111-112).

Compassion, in facilitative leadership, is a temporary suspension of judgment so that we come to truly understand them and honor them.

Honor: "Honor is the right way for us to treat others (Callahan & Martin, 2007, p. 53). Honor is to show respect for ourselves and our ideals, and to act within the confines of our ideals. Leaders characterized by the principle of honor are aware of and unthreatened by their own weaknesses. They are also unimpressed by their strengths and their talents. They see every interpersonal interaction as an opportunity to grow, and, more importantly, for others to grow as well. The desire to honor others is one of the points on their personal compass (Callahan & Martin, 2007, p. 54)

To be constrained by one's ideals is an important consideration. There may be times when intimidation or humiliation might be efficacious tactics for a leader to achieve their vision or goals, but engaging in these tactics would invite dishonor upon them. To be unthreatened by our own weaknesses is also to embrace the forgotten virtue of humility.

Humility: To be unimpressed with one strengths and talents displays humility, one of the cornerstones of Jim Collins' conception of the Level 5 Leader. Level 5 leaders represent, in Collins' model (2011), the pinnacle of leadership, and Level 5 leaders routinely credit others, external factors, and good luck for their companies' success. But when results are poor, they blame themselves. They also act quietly, calmly, and determinedly - relying on inspired standards, not inspiring charisma, to motivate (p. 118).

Collins goes on to describe the interviews with the transformative executives that led to the construction of the Level 5 leader. And what he observed was that

throughout our interviews with such executives, we were struck by the way that they talked about themselves - or rather, didn't talk about themselves. They go on and on about the company and contributions of other executives, but they would instinctively deflect discussion about their own role. When pressed to talk about themselves, they'd say things like, 'I hope I'm not sounding like a big shot,' or 'I don't think I can take much credit for what happened. We were blessed with marvelous people.' One Level 5 leader even asserted, 'There are a lot of people in this company who could do my job better than I do'” (Collins, 2011, p. 126).

And true humility is NOT to just say it, but sincerely mean it, and be grateful for the opportunity to lead.

Nowhere is this relationality captured more clearly than in Siemens, Dawson, and Eshleman’s article on complexity leadership. Siemens and Downes invented the concept of connectivism, and we see here the connections between people, networks, processes, and tools. These concepts of exchange, self-organization, feedback and economic impact are deeply relational. If you introduce a new tool, what new processes need to be built, and how will this impact people’s identity.

In the relational lens, some of the reflection questions to use to focus on the what is your most important relationship at work or at school? What is your most problematic relationship with your work? Is it with a process? A person? A tool? Who do you most need to forgive? What leadership education do you need to do?

Leadership is directional

Finally, leadership is directional. Leadership implies direction. How do we adapt our organizations to the dynamic changes taking place (a reactive position), and how do we sculpt and shape the world through persuasion, advocacy, and recognition of how the trends can be utilized to help us achieve our mission (a proactive position)? The directionality of leadership

Change, or adaptation, adaptive positioning, is extremely hard because there are many trends happening all at once. Each of these many political, economic, social, and technological changes impact our programs and the conduct of our business in some form or fashion.

This unalterable changefulness and irredeemable instability can alter patterns of dominance, and these external pressures are likely to create fissures and cracks that can be exploited through bargaining, negotiation, and jockeying for position. Within any postsecondary institution, power is structurally entrenched and unequally distributed. Executives hold greater influence over organizational vision, resource allocation, and advocacy with policymakers. But most postsecondary institutions also have managers with their vision of the future, along with faculty associations and other unionized employees that can and do exercise influence.

Slowly shifting patterns of dominance, such as Indigenization and the call for greater equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) in postsecondary education after tumultuous racial events in the United States and Canada stand in contrast to totalizing views of power. There are occasions when we lead the culture.

Some of the important questions to ask at this point are:

What trend do you think holds the most promise for your function, your department the college?

What internal/external advocacy needs to be done?

What leadership education needs to be done? How does this align with your leader’s goals?

What trend provides you more than few midnight anxieties about the future?What skills and equipment do the people who are going to be part of your expedition need?